|

Here is the past twelve months in a nutshell. More than 117,500 photos taken across 18 tracks in 3 states, 39 events and 37 written articles, this year has been my biggest year shooting motorsport and car culture. With so much covered, I thought I’d share with you the highlights of 2023, and some of my favourite photos of the year. Phillip Island HistoricsWe’ll start at Phillip Island, my favourite track to shoot. The Victorian Historic events have been on my radar for a while, but I’ve always missed them for one reason or another. This year I headed to the Phillip Island installment, which lines up conveniently with the Adelaide Motorsport Festival, so plenty of cars come internationally for both events. My aim was to find a few cars to spotlight and talk about. I’m pretty shy so I’d have to go out of my comfort zone and interview some owners and drivers. Thanks to working alongside Jack Houlihan and others for a couple of days at Street Machine Dag Challenge 2022, I knew a good way to go about it and I ended up interviewing 8 people and spotlighted ten cars from the weekend, so I was proud of that. Return to Calder ParkIt was great to see Calder Park returning to circuit racing calendars this year, but seeing a large field of NASCAR’s and AUSCAR’s racing at the National Circuit and doing laps of the Thunderdome was something truly special. I love NASCAR, particularly the old school cars, so seeing them roar on the Thunderdome, a racetrack I have photographed more than any other was awesome. Speaking with the drivers showed that this wasn’t going to be a one off, and the future of Calder Park is on the up. World Time Attack Challenge 2023Need I explain why WTAC is a highlight. It’s one of those events that you can be there for five minutes, and you’ve already decided to come back next year. You’ll see and experience things that you would have never imagined seeing. Shooting and writing for DownshiftAus, I was a busy boy, covering the time attack action, drifting and the Stylized show. Barton Mower and the RP968 team crushed the lap record, as Luke Veersma took the International Drifting Cup by storm. I got to meet and speak to Mike Burroughs from StanceWorks, Jeremiah Burton from Donut Media and got to photograph the Drift King himself, Keiichi Tsuchiya. Oh yeah, and there were plenty of cool cars to drool over too. Keep it Reet Battle Royale 2023 Ever since 2020, one of my goals has been to cover an entire season of drifting, and I finally was able to this year, shooting and writing about each of the four rounds of Keep it Reet’s Battle Royale season. Being invested in each round and seeing the championship play out before me, whilst making sure I covered all the big stories was a rewarding and cultivating experience. Street Machine Drag Challenge 2023The day before the Street Machine team headed to The Bend’s new dragstrip, Simon Telford called me unexpectedly saying they had a spare spot for an extra team member for their annual Drag Challenge. Obviously, I couldn’t say no, and before I knew it, I was shooting at the brand new Dragway at The Bend, photographing some of Australia’s fastest street cars! After check-in on Monday and the first day of competition on the Tuesday, we headed to Mildura for the 1/8th mile, then to the familiar Heathcote, then down to another 1/8th mile track at Portland. The racing would be rained out at South Coast Raceway, but the drive from Portland back to The Bend was spectacular, and I got to try some proper tracking shots. The highlight of the week was definitely Mark Whitla breaking into the 6’s and smashing the 200mph barrier, the first to do so in Drag Challenge history. It was an awesome week, and I learnt so much from the team of photographers/videographers at Street Machine. LZ World Tour AustraliaLess than a week later, I was covering Australia's biggest drift event, The LZ World Tour, for Drift Games. We started at the new Keep it Reet factory, revealing Adam's Australian 180SX, Mukka Motorsports 6-Rotor RX7 and the fresh wraps for Mad Mike's MX5 and the Keep it Reet Skylines. Things got a bit out of hand when LZ, Jason Ferron, Mad Mike and Benji Sneddon decided to all do burnouts, smoking out the factory. It honestly felt like being part of an old Hoonigan Daily Transmission episode. Onto the competition, and without doing a single qualifying lap, Mitch Larner would win the Last Chance Top 16 battles on the Saturday. On Sunday Adam LZ would win the main event, except his name would be Cam Marton, with Robert Arbolino second and Jordan Sanderson third. Nakai-san Builds RWB Australia #9 and #11October was full of surprises, and being able to photograph Nakai-san work was definitely not what I was expecting. I have been in awe of Nakai-san's work and RWB Porsches since I first discovered them on Speedhunters in 2017. It's one of those things that you always dream of experiencing, and then when it actually happens, you can't believe it. Favourite Photos of 2023GLE Racing had cracked a brake disc during qualifying at Winton, and I was there soaking up the brake change with my camera, getting plenty of shots, but this one is my favourite, with a bit more of a complex composition than my standard photo. The tools and parts in the foreground are cool as the curved bonnet lead the eye back to the mechanics. With the rain that had come before this year’s President Cup, the track surface started out a bit muddier than usual, with the support categories flinging up mud. I deployed my 150-500mm lens, but the track had been smoothed out, so I decided to get some close ups of the Sprintcars, during their qualifying runs. That was when Ross Jarred spun right in front of me keeping his foot in it, and I got the whole sequence. Right place, right time, right lens. With the darkness upon Heathcote Park, it was time to use my flash to experiment with some slow shutter pans. At the time, I didn’t know what I was doing, but now I know that the flash lit the rear of the car and the concrete wall, as there was enough light for the ¼ second pan to work. Another one from Holden Nationals, Grant Salter from Gripshiftslide took this shot, focusing on the hand on the handbrake. I love that shot, so now I’m always looking for working hands and details like that. At Holden Nationals, I got the shot I wanted. The team of this car opened the door so I could get a photo of their driver, focusing in on the hand, and getting one of my favourite monochromes of the year. I know, I know, this is the typical Phillip Island photo, but the 2007-08 FPR Falcons are some of my favourite race cars of all time, so seeing one in the flesh was completely unexpected. There are always lots of photographers at the end of the race getting snaps of the top three drivers, and particularly of the winner. It is often squished but I try and stay out of the way of those shooting for clients, magazines and the racing category itself, as most of the time, I am shooting just for myself. So, I have to look for different angles. I particularly like this candid of Josh Buchan after his win on the Saturday at Phillip Island, with his Hyundai i30N Sedan forming part of the foreground. When panning at slow shutter, and the car is quite close to you, you can get a lot of weird stuff, but on occasion, you can strike gold. Trying to focus on the number on the side of the GT3 cars, I captured Yassir Shahin/Garnet Patterson as their Porsche went over the top of Lukey Heights using a shutter speed of 1/4 of a second. Similarly, focusing on the helmet this time as Ryan Howe accelerated out of Turn 4 during the Australian Formula Open round at Sandown, this time at 1/10th of a second. Searching for different angles for the final race of the Superkarts weekend at Phillip Island, I found this view of the marshal post at the top of Lukey Heights at Phillip Island . Straight away I knew I'd edit it into a black and white silhouette, I just had to wait for a Formula F5000 car and for the marshal to step away from the fence, so he would be completely visible in the photo. For the LZ World Tour, I wanted to try something different. I mounted my camera to the top of fence above Calder Park's infamous 'Wall', getting a bird's eye view of the action. As only a couple of my photos showed the entire car, next time I need to angle the camera slightly higher, or use a wider lens, as this was taken at 23mm. When I took this photo, it made me remember why I love motorsport. Motorsport cannot be orchestrated or scripted, the craziness of competition happens naturally. I couldn't plan in my head to compose the photo like this: the bokeh from the fence, Chris Temby sending it wider than anyone else, the high sun, one wheel off the ground and Mitch Broome in hot pursuit. Sometimes the only thing you can do is put yourself in a good photo spot and just take photos as the cars come by. Then stuff like this happens naturally because motorsport is awesome. All you have to do is be there to witness it.

1 Comment

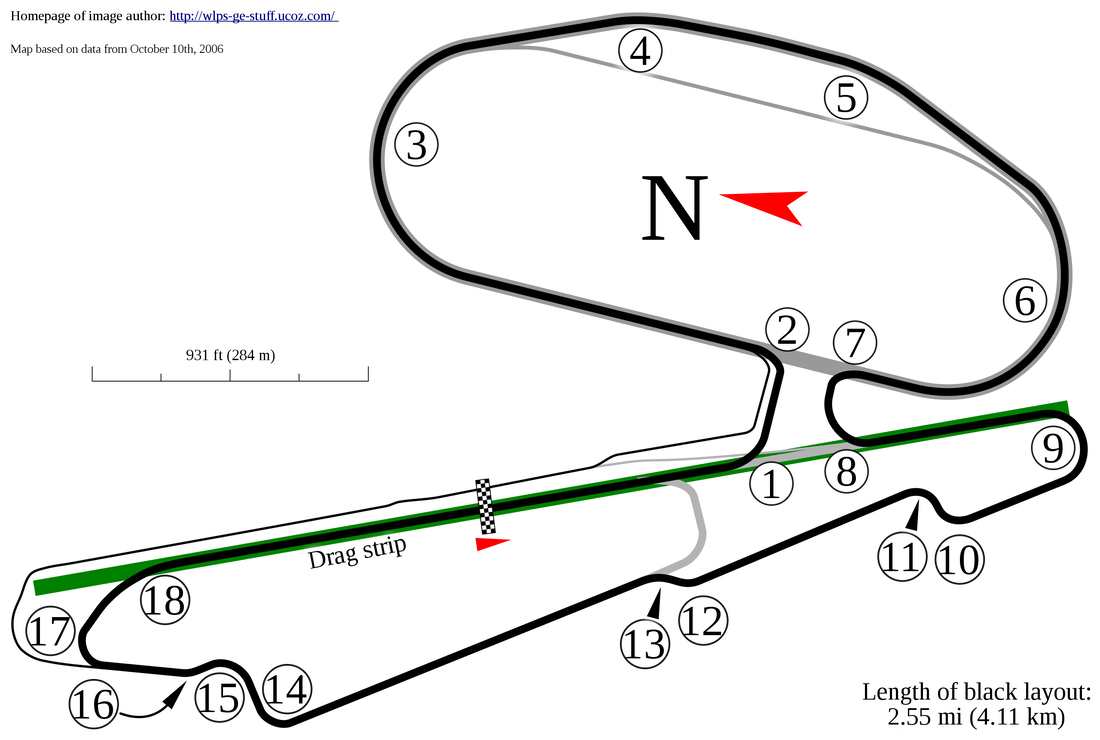

In the late 1980's, Australia had been bitten by the NASCAR bug. And a 1.1-mile superspeedway just across from a national park would be our home ground for Australia's version of Stock Car Racing, known aptly as 'The Thunderdome'. But before I speak about one of Australia's most unique racetracks, I should mention the complex it is a part of, the Calder Park Raceway. Like many motorsport complexes around the world, Calder Pak Raceway began as a simple dirt track, carved into the ground by local motoring enthusiasts wanting a place to race their FJ Holdens. The track was upgraded to bitumen with its first race meeting taking place on the 14th of January 1962, the layout being very close to what is now the north section of the Calder Park Road Course. During the 1970's tyre tycoon Bob Jane purchased the track, leading to the addition of a southern extension and at the time a rallycross track in the infield. Calder would also begin to host drag racing in addition. A decade later Calder's most prominent feature would be built, a 1.19-mile, 24-degree banked Superspeedway purpose built for modern Stock Car Racing, designed as a smaller version of Charlotte Motor Speedway in the US. Australia's only proper banked mile speedway was a result of Bob Jane striking a deal with NASCAR head honcho Bill France Jr to bring NASCAR down under. The new addition to the Calder Park Motorplex was opened in 1987, with its first race being the 1988 AUSCAR (Australian Stock Car Racing) 200, a 110-lap race one week before NASCAR's first event in Australia. 18-year-old Terri Sawyer would win the first race held at the Thunderdome in her yellow VK Commodore. What made AUSCAR different from NASCAR was the cars were lower spec stock cars, powered by a 5.0L V8 and based off home-built sedans like the Falcon and Commodore, whilst NASCAR was obviously American built cars, powered by 6.0L V8s. In addition, NASCAR raced anti-clockwise on ovals, whilst AUSCAR would race clockwise, due to the steering wheel being on the other side of the car. For NASCAR's first race outside North America, Goodyear would be the only tyre supplier because 1) they had the money and resources to ship tyres overseas, unlike the preferred manufacturer at the time, Hoosier and 2) Goodyear was the title sponsor of the race. Not all, but many drivers and teams would make the trip from the US to compete, with the rest of the field compiling of Australian speedway veterans and touring car legends such as Dick Johnson and Jim Richards. Neil Bonnet would win from pole in his Pontiac Grand Prix. Interestingly, 'The King' Richard Petty would lap the track in a private session with an average speed of 142.85mph, 3 miles faster than Bonnet's pole lap, setting an unofficial record at the time. NASCAR would return later that year for the Christmas 500, with Morgan Shepherd taking a four second victory over Sterling Marlin, the only driver left on the lead lap. Stock Car Racing would continue to grow in Australia in the 90's, with the Thunderdome's last NASCAR race being held in December 1999, a 60-lap sprint. AUSCAR would cease competition in 2001, leading to the slow demise of the track. Now, weeds fill the grandstands instead of race fans, the concrete has slowly shifted over time and the buildings have fallen into disrepair. V8 Supercars haven't raced at the road course since 2001 and recently Drag Racing has had a sabbatical from the drag strip. However, from 2004 to today, a new form of motorsport would compete at the Calder Park Motorsport Complex: Drifting! Using pretty much every section of racetrack at Calder, this cheaper form of motorsport would become the main attraction at not only the Thunderdome, but the road course as well. The most used layout is the FD Layout, first used in 2013 as part of the Australian round of the Formula Drift Asia championship (Yes this is my favourite Calder Park fact and I will continue to mention it at every possible moment). The other layout which shares the same final tight hairpin is the DCA Layout, used for the past Drift Challenge Australia rounds. The Road Course has the most layouts however, using every section of tarmac with Reverse over the Hill, Run the Gauntlet, Keep it Reet's new DT Layout, Run the Wall (using the drag strip end of the circuit) and the Crossover (using the section of track connecting the Road Course to the Thunderdome). In the past 12 months, Calder Park has seen a rise in motorsport events. With more drifting organisations such as Keep it Reet, DriftCadet and now DriftWorx holding more frequent, larger and newer style events at the circuit. Track Days have also returned, with MotorEvents Racing holding a grassroots endurance race on the Dome late last year. Drag Racing is also set to return in the coming weeks with weekly Fast Friday Street Drags (if it can stop raining that is). Although the complex is far from being in a good state, it is great to see motorsport still being enjoyed at the very unique Calder Park Raceway. There have been many calls for many years to see Calder Park refurbished and returned to its glory days, but we are far from that. It will be a very long time, if ever, when we see the return of V8 Supercars to the Road Course but the track also seems to be distancing itself to from the prospect of being completely fruitless. After Covid and more than 15 years of rumours of the track being demolished to make way for housing, to see it still standing and holding frequent events, of now multiple disciplines is a great thing to see and certainly a step in the right direction. I hope we can enjoy Calder Park for many years to come.

To contribute to Calder Park's future, be a part of the Petition to 'Save Calder Park' via Change.org The Bathurst 1000 has seen some unpredictable and wild moments in its long history that have come to define the race and Australian motorsport as a whole. There are plenty of reasons why the Bathurst 1000 draws motor racing fans from all over. Here are ten moments from the race's long history that keep bringing us back every year. Click on the titles to watch them on Youtube. The Rookie and The ProThe 2011 Bathurst 1000 would be a baptism of fire for rookie Nick Percat, driving alongside veteran Garth Tander in the Holden Racing Team no. 2 Commodore. After starting ninth, they would be up the front for most of the race, with Percat learning and impressing as he held on among the frontrunners, despite a scary moment with contact coming out of Turn 2. As the race wound down, Percat would finish his final stint giving the reigns to Tander. As Safety Cars bred chaos, Tander would hold off Craig Lowndes to the final corner, winning the race by two tenths of a second, one of the closest finishes in Bathurst history. The Failed RedressHow do you take three competitive cars out of contention in a couple of corners? Just ask Jamie Whincup. Although he’s one of the most successful V8 Supercar drivers, he has missed out on a chance at hoisting the Peter Brock Trophy a handful of times. 2016 would be one of those examples. Jamie Whincup and Paul Dumbrell would start on pole, alongside Scott McLaughlin and David Wall. The two fastest cars in qualifying would still find themselves locked in battle on lap 150 of the 161-lap race. Whincup would dive down the inside of McLaughlin at the Chase with Garth Tander right behind in third. The dive would force McLaughlin’s GRM Commodore off the track. Whincup would slow to let him join the track ahead, however, this would compromise Tander, and the three leaders would collide. McLaughlin would spin into the wall and Tander would be out of the race completely. Jamie Whincup would receive a 15-second penalty, meaning he had to finish 15 seconds ahead of second place Will Davidson to win. However, another Safety Car for Todd Kelly stranded in the gravel would halt Whincup’s charge. With the penalty, Jamie Whincup and Paul Dumbrell would be classified 11th as Davidson and Jonathon Webb would hold off Shane Van Gisbergen to win the great race by a paper thin 0.14 seconds! Dick Johnson and The RockMotorsport is quite unpredictable if you didn’t know. There are several factors that can take a driver and team out of the lead of the race: Mechanical failures, a driver mistake or strategy being flipped on its head thanks to changing racing conditions. Or you could crash into a rock that had rolled onto the track that some spectators had been leaning on! Does that sound too specific? Because that is exactly what happened to Dick Johnson. After starting second and grabbing an early lead, Lap 17 would be when it went all badly wrong. With a truck picking up a broken car, Johnson had nowhere to go but hit a boulder that had found itself on the track, causing his Ford Falcon to go airborne and into the wall, ending his race. Bathurst 1000 telecast would then become a mix of race coverage and a telethon from fans donating enough money for Dick Johnson to rebuild his car. And despite Johnson thinking he'd had enough of racing thanks to bad luck; he’s been a part of the V8 Supercars ever since. Murphy's Lap of the godsWhen it came to qualifying, Ayrton Senna was the master of Monaco, Rick Mears was ‘The Rocket’ at Indy, and Greg Murphy was the fastest at the Mountain. This he proved in 2003 with what is dubbed ‘the lap of the gods’. He had been fastest in multiple practice sessions and the first stage of qualifying. However, the task of beating John Bowe’s 2:07.956 during the Top 10 shootout “looked as big as the mountain he was about to tame.” So, everyone was glued to their screens when Greg Murphy went faster by four tenths of a second in just the first sector. Passing the second sector mark, he was almost seven tenths up. He would cross the line with a time of 2:06.859, a lap record at the time and beating Bowe by a staggering 1.09 seconds! Take a bow Greg Murphy, that was something very special in the history of Bathurst!” – Matt White From Last to the Turn 2 Wall… Then Victory LaneChaz Mostert and Paul Morris would start from the back of the grid after being disqualified from qualifying for breaching the red flag conditions. To pass them off as a non-factor for the race win wouldn’t have been unkind, particularly when Paul Morris found the Turn 2 wall, and was lucky to continue. But they did have a fast car, and by the end of the race, whilst the main contenders had all fallen to the wayside, it was Chaz Mostert hunting down the low on fuel Whincup in what would turn out to be one of the greatest finishes in Bathurst history. 1000km’s of endurance racing would all come down to a single lap around the Mountain. Farewell to The KingNo driver defines Australian motorsport and the Bathurst 1000 more than 9-time winner Peter Brock. His legacy and imprint on Holden and the V8 Supercars are immeasurable, not to mention his student, Craig Lowndes. On September 8, 2006, Brock would be killed during the Targa West rally. That October at Bathurst there would be an outpouring of emotion and tributes to the King of the Mountain. It’s time to say farewell to Peter, in the way he would have wanted. Let’s go racing on the Mountain!” – Leigh Diffey Lowndes would pick up three spots into Turn 1 of the race and by lap 25, would have a six second lead. Using all of Brock’s lessons, both Lowndes and Whincup would be up front all day as a key contender for the win. With 15 laps to go, Lowndes had a 7 second lead to Rick Kelly, but the field would be bunched up one more time with 7 laps to go. Lowndes, however, was just too good, hoisting the new Peter Brock trophy on the podium. Lowndes [and Whincup] have done it! On the day he farewelled his friend!” – Leigh Diffey Godzilla The EnemyThe Nissan Skyline R32 GTR was coined by Australian journalists as Godzilla. Not because it was awesome beast, but because its dominance was seemingly destroying Australian cars in a bad way. The 1992 Bathurst 1000 would only increase this notion and the hatred of the GTR by Holden and Ford faithfuls. On lap 143, rain and hail would drench the track and surrounding suburbs, and soon enough many cars would find themselves in the wall. The race was declared finished on lap 145. Jim Richards in the No.1 GTR would find himself in a pile of cars on the back straight, whilst Dick Johnson in the Ford Sierra would cross the line, thinking he’d won. However, as were the rules back then, the race would be backdated to the last lap before the need for a red flag, giving the win to Richards and Mark Skaife in the GTR. Fans were not happy and showed their disapproval with loud booing as Richards & Skaife climbed onto the podium. Not happy with the reception, Jim Richards gave us what now are some of the most famous words spoken at the Mountain: I thought Australian race fans had a lot more to go than this… This is bloody disgraceful.. You’re a pack of assholes!” – Jim Richards The XB Falcon DominatesThis was the year that Ford was saved at Bathurst. The new XB Falcon dominated the race unlike anything that had come before it. However, the real story comes near the end of the race, as Alan Moffat would suffer from failing brakes. and as he was the team boss as well, he ordered Colin Bond in the No.2 XB Falcon to hold station as they drove side by side for the final lap to the chequered flag, just as Ford had done at Le Mans in 1966. Slick Track Causes Chaos“We’ve been waiting for this race to explode and now it has!” With 20 laps to go in 2007’s instalment of the Bathurst 1000, Jason Bright had a 28 second lead, but would have to pit for a splash of fuel to make it to the end. Mark Winterbottom and Steven Richards were second, with Craig Lowndes breathing down their necks. Rain started to fall with 16 laps to go, and two laps later, Paul Morris would spin at ‘The Cutting’, bringing out the safety car, and turning the race on its head. The Britek Motorsport team would take this opportunity to fill Bright up with fuel and change tyres, not rain tyres, but cold slicks, on a wet track. The Safety Car bunched up the field and let the V8 Supercar field continue their battle on lap 148. Now the race would explode. Winterbottom being the first to experience how wet it was on the back straight, would send it through the gravel trap at the Chase, almost taking out second place Lowndes and surrendering the lead. Everyone was on slick tyres, but Bright on fresh cold ones was struggling to find any grip. Their race would turn further upside down when Jason Bright would slide into the wall at McPhillamy, with Russell Ingall and Mark Skaife following suite. After another Safety Car restart, Lowndes and Steven Johnson would battle for the lead, side by side on the slick track. James Courtney would join the battle when Lowndes made a gutsy move into Turn 1. But there was no stopping Craig Lowndes, with Jamie Whinchup as co-driver, they would score back-to-back Bathurst wins. Balaclava-GateMotor racing teams and drivers aren’t very good at being sneaky or deceptive. Think back to the 2010 German GP, when Ferrari wanted to swap their driver's position (which wasn’t allowed at the time), so they gave Felipe Massa a coded message. That being “Fernando is faster than you, can you confirm you understand this message”. Ferrari would be fined $100,000 for interfering with the final race results. Even more hilarious and pathetic was DJR’s attempt at backing up the field near the end of the 2019 Bathurst 1000 so they wouldn’t be affected by having to double stack their cars. However, what takes the cake is what happened to Stone Brothers Racing and Marcos Ambrose in 2005, as they were a favourite for the win that day. On lap 102, race officials would be questioning Ambrose’s co-driver as to whether he had been wearing his balaclava (fire protection for the head) during his previous stint in the car. Unable to prove without doubt that he had been wearing it, the No.1 Falcon was given a drive through penalty, as officials attempted to find out through video footage if Ambrose himself was wearing one also. Finally on lap 119, the question was asked directly to Ambrose. Marcos… are you wearing your balaclava there now?” He wasn’t, and on lap 122 Ambrose would come in to put on his balaclava. It would get worse however as on the safety car restart, Ambrose and Murphy would collide at Turn 3, blocking the track and going head-to-head in more ways than one. Murphy was fuming, and Ambrose had had enough.

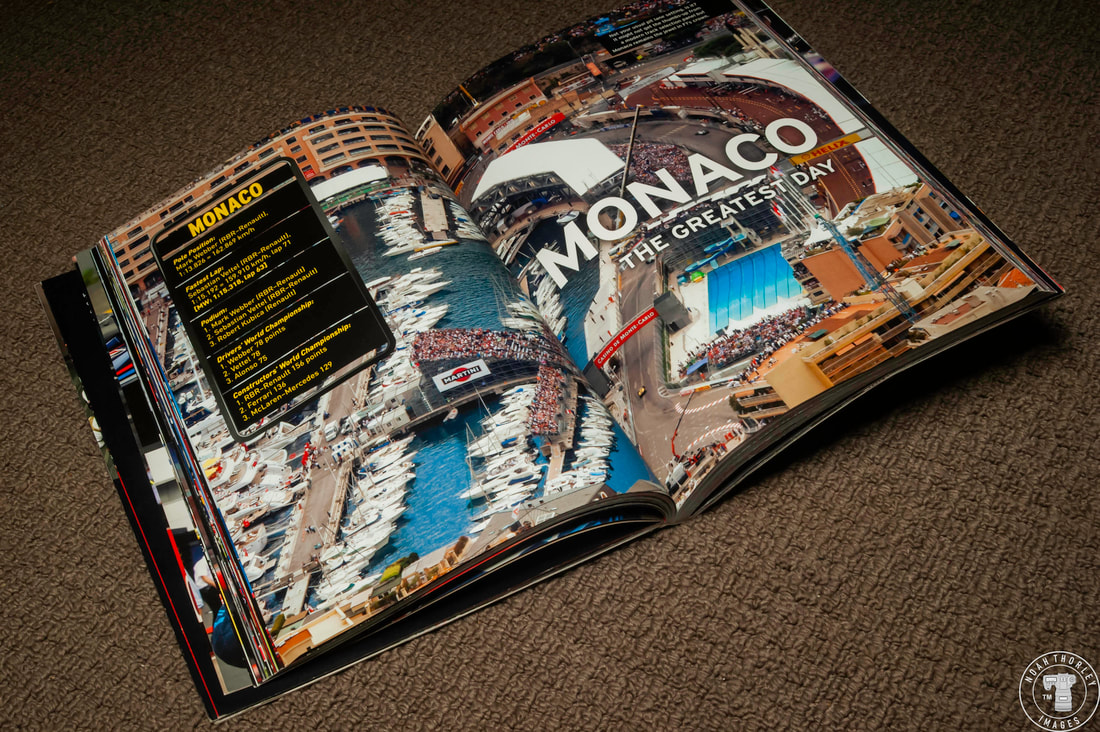

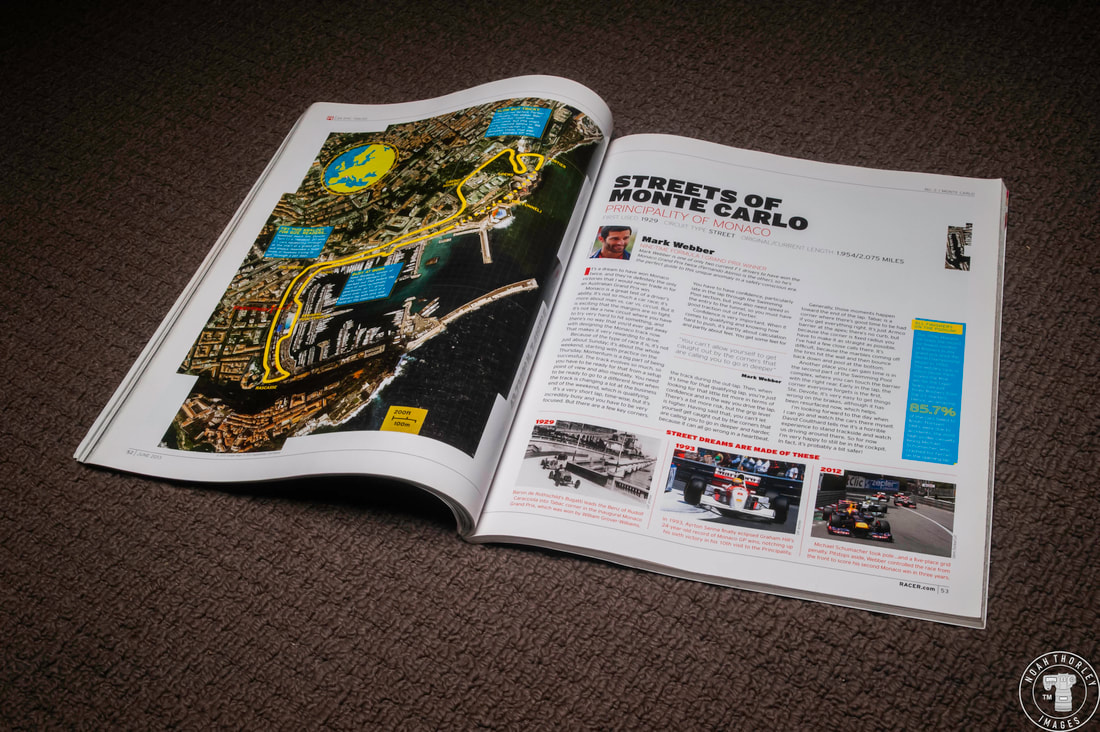

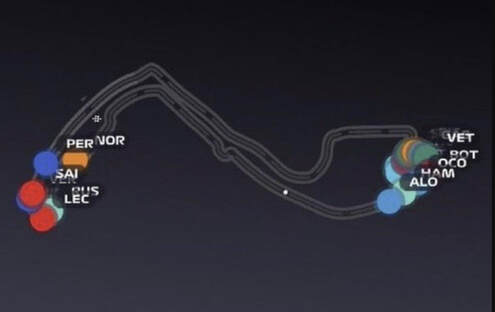

Formula 1 and IndyCar are the two top open wheel championships in the motorsport world. Although they differ enough to discourage comparisons that try to determine which series is better, IndyCar can learn a lot from Formula 1. And so too can Formula 1 learn a lot from IndyCar. I bring this up because this week, the FIA released next year’s Formula 1 calendar and the announcement that the Monaco Grand Prix would stay on the calendar for the next three years. Honestly, the Monaco GP and Formula 1 shouldn’t be in a position to question the future of one of the most historic races. It’s absurd. Which is why these next three years are going to be crucial as the Monaco GP continues to be up for debate. The Monaco Grand Prix has been around and held around the streets of the Monte Carlo harbour since 1929. It is one of the longest ongoing motorsport events and is part of the triple crown (Indianapolis 500, 24 Hours of Le Mans and Monaco Grand Prix). It is no doubt a crown jewel of a race. It should be the most important race in Formula 1. If you can’t win the championship, you at least should want to win at Monaco. This is just how the Indy 500, Le Mans 24 Hours and Daytona 500 are seen by competitors: a special single race that immediately plants your name in the history books alongside many other racing legends. Yet the prestige of winning at Monaco has dwindled. There is no song and dance or magnified anticipation for this special race. Despite its long history and challenging racetrack, the Monaco GP feels like any normal Formula 1 race. It is even met often with pessimism from fans. That’s why Formula 1 needs to make sure the Monaco Grand Prix is not only seen as a crown jewel of motorsport but becomes one as well. Formula 1 needs to take a page out of IndyCar’s book. The Indianapolis 500 follows weeks of anticipation with plenty of media coverage hyping up the race and looking back at its long and spectacular history, a parade through downtown Indianapolis and lots of track time. The festivities before the infamous call to start engines create an atmosphere like nothing else. This is what Formula 1 should aim for with Monaco. The good thing is my first point about looking back at legends and the races history is already done with the Monaco Historic Grand Prix a of couple weeks before... a feature of classic Formula 1 cars blazing around the principality once more. Yet it seems very detached from the actual FIA sanctioned Monaco GP and as far as I know Formula 1 doesn’t cover this event in its media coverage even though it is the perfect opportunity to enthrall and hype up fans for the race. The only reason the event made it in the news this year was because Charles Leclerc had a brake failure whilst driving Niki Lauda’s 1974 Ferrari. And the only reason I knew of this event was thanks to photographers Matty White and Tom Shaxson on Instagram. The common opinion of Monaco is that it is a boring race, because of how difficult it is to overtake, and yes, this is very true. This year’s race saw a hilarious train of cars circulating the track unable to pass one another. However, Monaco has produced some bonkers races and unpredictable moments in previous Formula 1 seasons. Red Bull forgetting to get the tyres ready for Ricciardo, causing him to lose the race he was dominating, then getting redemption two years later with only 75% engine power is a fairy tale story. Monaco produced a race full of carnage in 1996 as only three cars finished. It has produced surprising race winners such as Oliver Panis and Jarno Trulli. And there is often carnage at the first corner as drivers attempt heroics into Sainte Devote. Monaco pretty much was where the legend of Ayrton Senna was created, with his charge to second in the slow Toleman, six further wins at the track (a record) and his qualifying lap in 1990 that would be known as one of the greatest laps in F1 history. He would also hold off Nigel Mansell in the superiorly quick Williams in 1992. Monaco can produce great races, just like any other track. Yet also like any other track, it will have its dull ones too. But like I’ve said before, that is what makes the fantastic races even more special. I also believe that people forget how much they actually enjoy seeing Formula 1 cars fly around this tight and twisty circuit. Around the time of the Grand Prix every year, I see multiple posts and videos of how close these drivers get to the walls around Monaco, with comments in awe of the driving talent on display. Monaco Grand Prix qualifying is also the best qualifying session of the year, because seeing drivers push their cars to the limit on this unforgiving circuit is a wonder to behold. And that is also what I think fans forget too. The appeal of motorsport isn’t just when exciting racing occurs but also seeing the most technological advanced motor vehicles being hustled around by talented drivers. Ever since motorsport began in France back in 1895, that was the main appeal. And the Monaco Grand Prix provides just that! 1.6 million people tuned in to watch this year’s Monaco Grand Prix, the second largest in the race's long history, despite the rain delay and the stewards having one of their brain farts again. It is an anomaly in the modern motorsport world, and we are extremely lucky that this bonkers racetrack is still around today, in a world where new tracks have miles of carpark like run-off and smooth asphalt rather than gravel traps and armco barriers. Formula 1 has rapidly grown in the past few years thanks to Liberty Media and the ‘Drive to Survive’ Netflix series. Now is the perfect time to share and make the Monaco Grand Prix a serious and fantastic race with an amazing atmosphere and a much larger media coverage. Formula 1 are already working on making the cars smaller and easier to pass, which is the main problem the Monaco GP faces. New regulations will be applied for the 2026 season. That is why the time is now for Formula 1 to make the Monaco Grand Prix a crown jewel of motorsport, just like it was and should always be, to be ready for the better cars and hopefully better races.

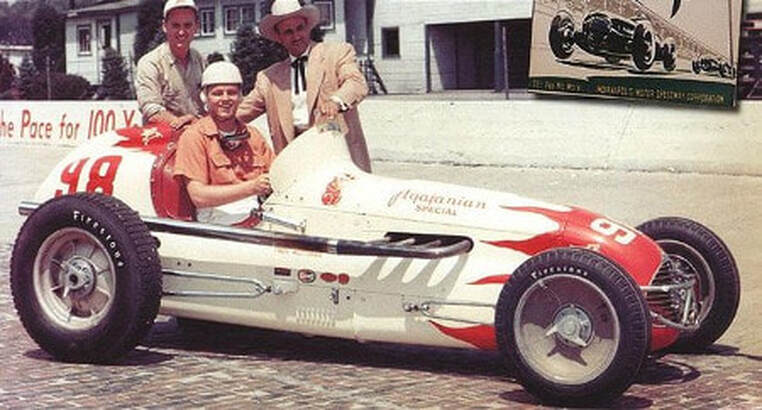

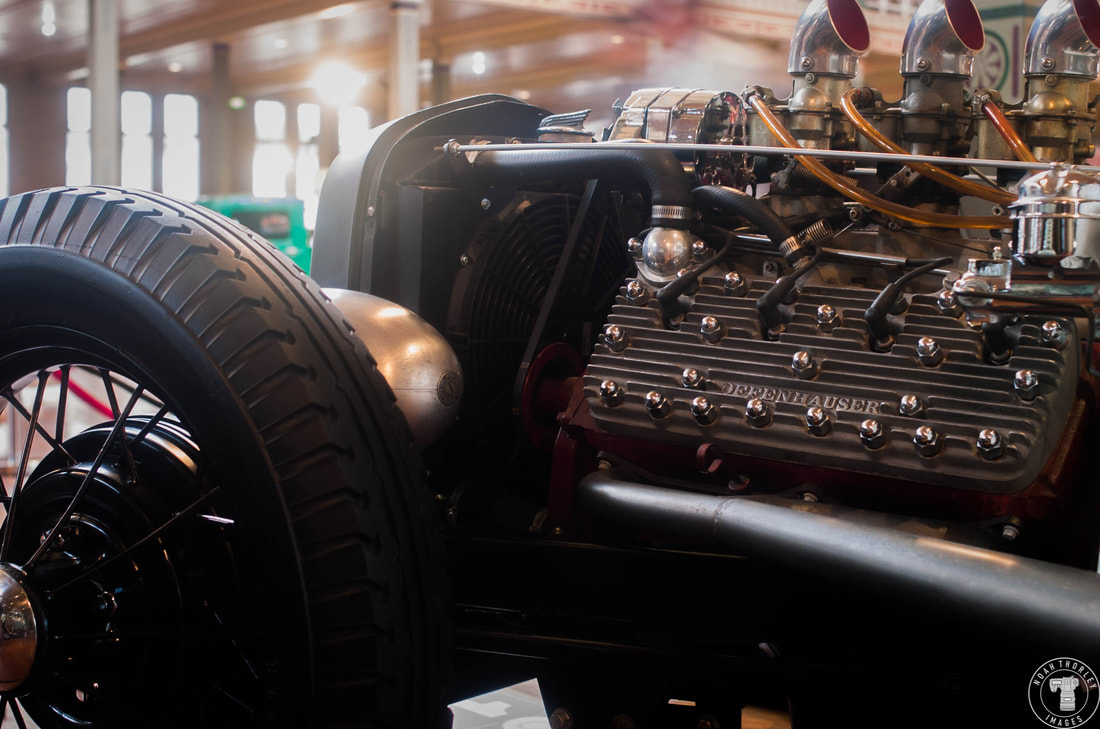

I’ve already gone over how F1 statistics can sometimes be confusing and unnecessarily complicated in a previous editorial. This time, I want to go over a few more facts and stats that can be considered discrepancies or anomalies, ones you may not have heard of before. Because, for the first eleven years of Formula One’s history, the Indianapolis 500 was part of the F1 calendar as a points paying race. Let’s start at the beginning, 1950, the first F1 World Driver’s Championship. Giuseppe Farina would win the championship, and an Alfa Romeo would take the victory in every race that season. Except the Indianapolis 500. Because most of the Formula 1 calendar was based in Europe, not many during this decade travelled to the U.S to participate in the American round of the F1 Championship. This meant that American based drivers would earn points in a championship that was mostly based in the European continent. Allowing them to also hold some unique records and milestones. Kurtis Kraft was the only car to stain the Alfa Romeo dominance, whilst Johnnie Parsons would be the first American to win in F1. The 1950 Indianapolis 500 would also be the first race in F1 history to be shortened, as only 138 laps were completed when rain stopped proceedings. In the past 20 years, many drivers have broken the record for being the youngest race winner in F1. Lewis Hamilton, Sebastian Vettel and now Max Verstappen have all held this record at some point. However, from early in F1’s history, that record was held by 22-year-old Troy Ruttman, who won the 1952 Indianapolis 500. It would take 51 years for that record to be broken by Fernando Alonso in 2003. Jim Clark holds an impressive statistic. He led 49.5% of the laps in F1 races that he competed in. This means that he was in the lead of the race for almost half of the laps he raced in. But someone from America tops that record, bringing it into untouchable territory. Bill Vukovich would compete in his first Indy 500 in 1951, lasting 29 laps until suffering an oil leak. In 1952, he led 150 of the 200 laps before suffering a steering failure. In 1953, during the hottest race on record at the time, Vukovich would lead 195 laps to win his first Indy 500. He would win again the following year leading 90 laps. In 1955, Vukovich would lead 50 laps before being fatally killed on lap 56. An innocent bystander with no way of avoiding the crash. Overall, he would lead 485 of the 676 laps he raced, 71.7% demolishing Jim Clark’s record. Because he only raced in the Indianapolis 500, this meant he would have won 40% of the F1 races he competed in and led 80% of those races. Unthinkable numbers that people often disregard. Another interesting fact, although I can’t quite identify if it is 100% true, but because the 1953 Indianapolis 500 was so hot, and with the driver’s feet inches from the large and very hot combusting engines, many teams had relief drivers. The race had become one of endurance like Le Mans, with up to 5 drivers sharing the duties across one car. Which I would assume would be the most drivers to share one car in a single F1 championship race. Back to 1952 though. I’ve already mentioned that it was difficult for teams and drivers to compete in the European races and the Indy 500. Ferrari were the first team to do both. Alberto Ascari would miss out on the Swiss Grand Prix, as he was at Indianapolis practicing and qualifying for the Indy 500, whilst his Ferrari teammates Piero Taruffi and Guiseppe Farina would race in Switzerland for the first race of the season. This means that it took three seasons for a team to compete in a full season, and that team was Ferrari. Ascari would race the Ferrari 375 with its V12 engine. Because the Indy 500 was sanctioned under USAC rules and not the FIA, the new regulations imposed on teams that year didn’t affect the Indy 500. This meant that Enzo Ferrari could send the faster Ferrari 375 with its V12 engine to Indianapolis, whilst the new Ferrari 500 with an inline four would race in the European rounds. He would qualify nineteenth and would climb through the field quite quickly. Unfortunately, he would retire due to the conventional wire wheels not being strong enough to sustain the bumpy brick surface of the Indianapolis Motor Speedway. As Ascari would win every race after that season, this would make him the first F1 champion to also race at Indianapolis. No one would compete in every race of the F1 championship until 1961, when the Indy 500 was no longer on the calendar. Juan Manual Fangio, five-time F1 champion attempted this feat in 1958 but failed to qualify for the 500. Across the eleven years that the Indy 500 was part of the Formula One Season, the Offenhauser engine would power the winner of every Indy 500 from 1950-1960. The engine would also be entered in 11 other F1 races in its history, however, would have a best finish of 10th in those races. However, its success at the Brickyard would mean that Offenhauser has a 50%-win rate during its time in Formula 1. I’m not sure any other engine manufacturer can come close to that.

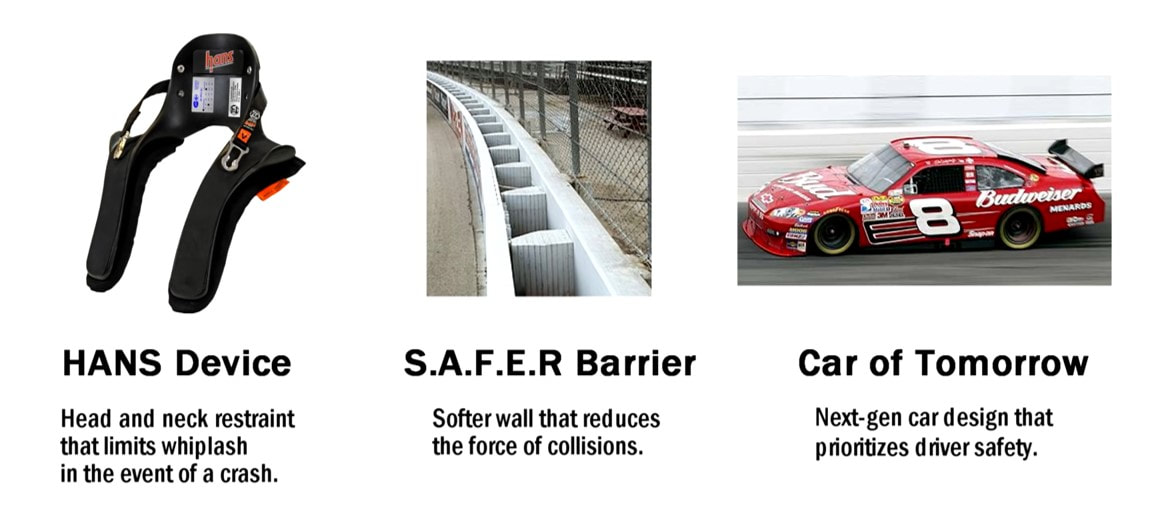

Interestingly, once the Indy 500 was off the Formula 1 calendar, there was suddenly more interest from Europe. Colin Chapman with Graham Hill and Jim Clark would start the British Invasion, and turn the racing on its head, bringing the rear-engine revolution with it. More drivers from the European circuit and abroad would come to compete in the 500, including drivers like Jack Brabham, Jochen Rindt, Clay Regazzoni and teams like McLaren. Now, there are more overseas drivers competing in the Indianapolis 500 each year than American drivers. F1 drivers would also make the full switch to American Open Wheel racing, such as Emerson Fittipaldi, Eddie Cheever, Takuma Sato and more recently, Marcus Ericsson, Max Chilton, and Alexander Rossi to name a few. February 18, 2001. The 43rd Running of the Dayton 500 would be one of the greatest races in NASCAR. But that 18th day in February would be tarnished with one of the most unexpected and saddest tragedies in motorsport. 150,000 people had packed themselves into Daytona International Speedway. The race was anticipated to be the best Daytona 500 to date. Perfect weather, paired with a new form of restrictor plate to keep the competition close. FOX and NASCAR had pulled out all the stops to cover the race on television as 17 million watched from afar. I think it’s going to be some exiting racing. You’re going to see probably something you’ve never seen.” - Dale Earnhardt Speaking of ‘The Intimidator’ Dale Earnhardt, 3 years prior, he had set up a new race team, D.E.I (Dale Earnhardt Incorporated). In 2001 the team would consist of his son Dale Earnhardt Jr, Steve Park (1997 Busch Series Rookie of the Year) and Michael Waltrip, who after 462 races, didn’t have a single win. Waltrip would race in his older brother’s shadow, but Earnhardt saw something in him, hiring him for the 2001 season. In addition, racing with his son had sparked a new flame in Earnhardt, and he seemed to take more appreciation in Dale Jr’s accomplishments than his own. Dale Earnhardt was a 7-time NASCAR champion, tying him with ‘The King’ Richard Petty. He was the best restrictor plate racer in history, dominant at superspeedways like Daytona and Talladega. He had famously conquered the 500 in 1998. He was the most influential driver in NASCAR history, yet he now had a different shine, and continued to impress those who rooted and booed for him. As teams made final preparations and drivers brought their stock cars to life, Darrel Waltrip summarised what it’s like to win the Great American Race. Some dreams turn into nightmares… But there’s no greater feeling, no greater accomplishment than driving your car through those pearly gates, into that holy ground.” - Darrell Waltrip How eerie those words sound now. ‘Awesome Bill from Dawsonville’ Elliot lead the 43 determined drivers and their horsepower hungry chariots as the green flag waved. Straight away it became obvious the afternoon would be filled with close door to door racing at 180mph, only judged by the air around them and the courage of the drivers. It didn’t take long for there to be multiple changes for the lead as drivers went up and down the order. Dale Earnhardt spectacularly pushed his way forward, almost on the grass to take the lead on Lap 3. Dale Jr would soon join his father near the front of the pack. The first caution would come when Jeff Purvis slid into the wall in the no. 51 Phoenix Racing Dodge. This would give everyone a chance to pit for fuel and new tyres. For the next 105 laps, fans were treated to more close racing and constant lead changes. It would only be a matter of time before the drivers would find the limit. Dale Jarret would drive blind and save his skin as others flew off into the pit lane, almost causing a collision. On lap 157, Kurt Busch would be punted into the wall when he moved in front of Joe Nemechek. He would then slide dramatically into the infield, bringing out the caution and bunching up the pack once more. Soon after, on Lap 173, ‘The Big One’. Contact between Robby Gordon, Tony Stewart and Ward Burton began a chain reaction down the backstraight. 18 cars were collected in the mess. Tony Stewart had flown and rolled multiple times in the crash. The back straightaway had become a wrecker’s yard, and the race would be red flagged to clean up the pile of futile steel and rubber. Everyone came out of the wreck okay. The race would restart on lap 180. Dale Earnhardt would lead the field to green. Sterling Marlin would take the lead, until Michael Waltrip regained the lead again in his no. 15 D.E.I car. With 5 laps to go, Michael Waltrip would lead, with teammate Dale Jr right behind. In third was Dale Earnhardt, but Earnhardt would be playing chess. Something probably never seen before. Rather than do anything to win, Dale Earnhardt, ‘The Intimidator’ would be keeping the rest of the pack behind, protecting his team. Coming out of Turn 4, the two D.E.I cars would race to the chequered flag as a crash faded the competition away. It was just Waltrip and Dale Jr racing to the chequered flag. In the commentary booth, Darrell Waltrip, 3-time NASCAR Champion and 1989 Daytona 500 winner, would call the final lap, rooting for his younger brother Michael. Keep it low Mikey, don’t let them under you” After 463 races, Michael Waltrip had not only grabbed his first NASCAR Cup Series win, but the greatest of them all, the Daytona 500. You couldn’t script this if you tried. Nor would you want to write the tragedy that came next. NASCAR President Mike Helton stands in the media centre, surrounded by microphones, journalists, and camera crews. His serious eyes and moustache hide any emotion, but not for long. Flash bulbs are going off as he sways slightly from side to side. This is undoubtedly one of the hardest announcements I’ve ever had to make. But after the accident at Turn 4 at the end of the Daytona 500, we’ve lost Dale Earnhardt.” - Mike Helton (NASCAR President) Battling with Sterling Marlin and Ken Schrader as his team raced ahead to the chequered flag, Dale Earnhardt crashed head on into the Turn 4 wall. He suffered a basilar skull fracture, sustained from blunt force trauma, killing him instantly. Regrettably, the same injury that had caused the deaths of Adam Petty, Tony Roper, Kenny Irwin Jr. and Blaze Alexander. Life can give plenty, but often it takes more. But there is some solace. The last thing Earnhardt would have seen would be Michael Waltrip, a driver everyone but him had doubted and lost faith in, lead his son to the finish line of a race that had alluded Earnhardt for 20 years, despite being the best racer on these types of circuits. He had nothing more to accomplish. We would never see his performance and awe decline. That’s what makes him a legend. I think Dale Earnhardt would have been content with that. However, NASCAR and its fans would need time to heal. This would come in a matter of stages. The following race at Rockingham, Steve Park, the third driver for D.E.I would take victory, their second straight win of the season. Two from two. Park would wave a number 3 Earnhardt cap out the window of his car on his drive to victory lane. Richard Childress would bring in a young Kevin Harvick to drive the new no. 29 car to fill in the vacancy left by Earnhardt. In almost a carbon copy finish to how Earnhardt had won the race a year prior, Harvick would claim victory in only his third start. Similarly, to Steve Park’s celebration, Harvick would hold three fingers out of the cockpit, saluting Dale Earnhardt. The fans did the same, and it has become a tradition to do so, especially on lap 3 of each year's Daytona 500. He also paid tribute to Alan Kulwicki, by driving a lap in reverse so he could more easily wave to the fans, a signature celebration used by Kulwicki who also was taken to soon. When NASCAR returned to Daytona for the July race, Dale Jr and Michael Waltrip would finish as they did in that year’s 500. Yet it would be Dale Jr who would take victory, Waltrip second, at the track that took ‘The Intimidator’ only months prior. D.E.I would dominate at superspeedway tracks for three years, just like Earnhardt had done his entire career. In 2003, Waltrip would win the Daytona 500 again, and a year later, Dale Jr would claim victory in NASCAR’s most prestigious race. This was enough to heal the wounds of many fans. So thankful, so thankful for Dale Earnhardt. He made [Daytona] even more special to me... And I know his heart, he was about this place. And I know he's smiling now" - Michael Waltrip after winning the 2003 Daytona 500. In the wake of the tragedy of February 18 2001, NASCAR would implement a number of safety features including a much safer and stronger spec car, called the ‘Car of Tomorrow’, the HANS device (Head and Neck restraint) and the S.A.F.E.R barrier, to soften impacts.

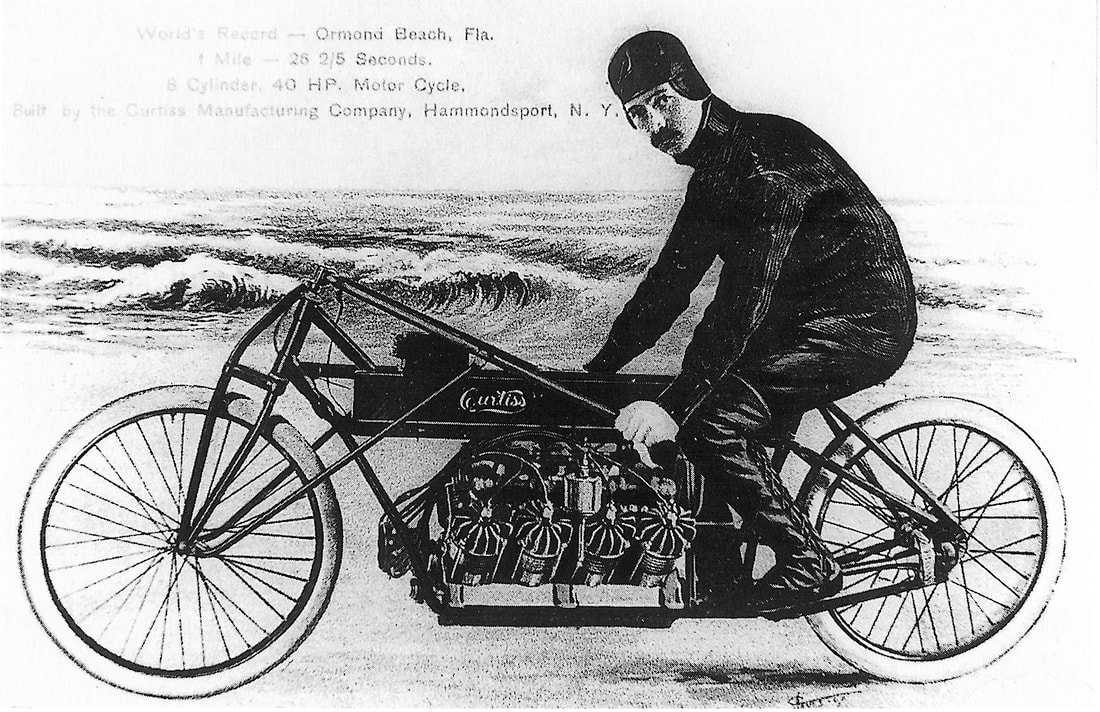

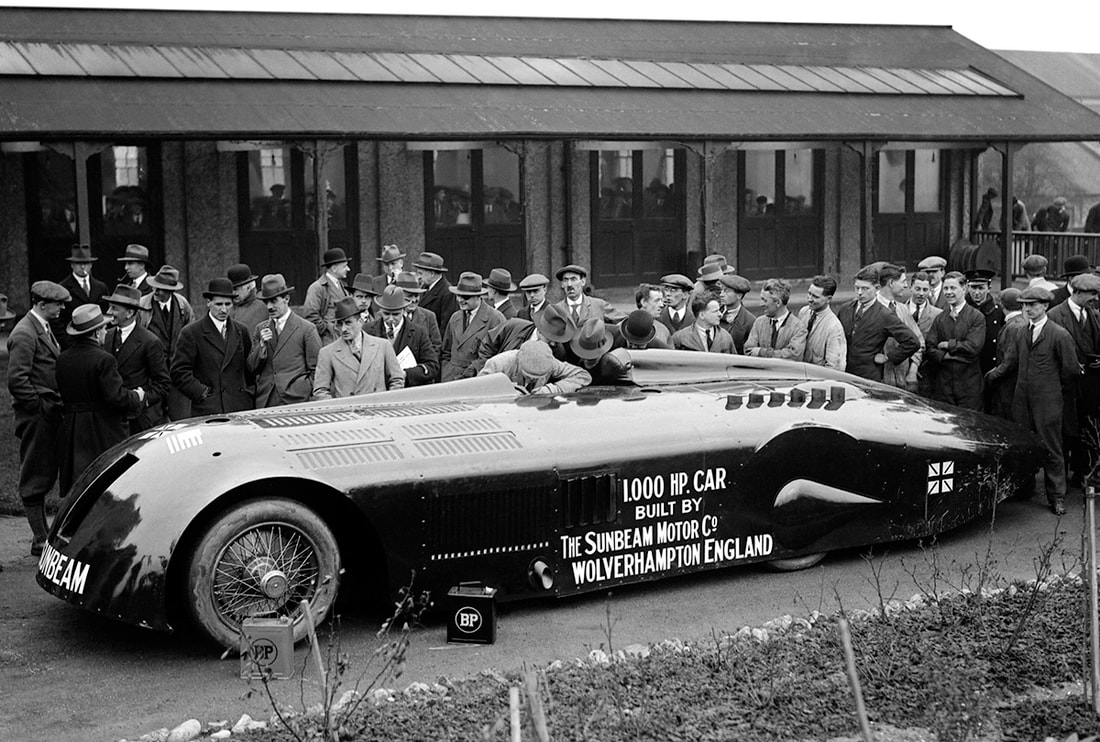

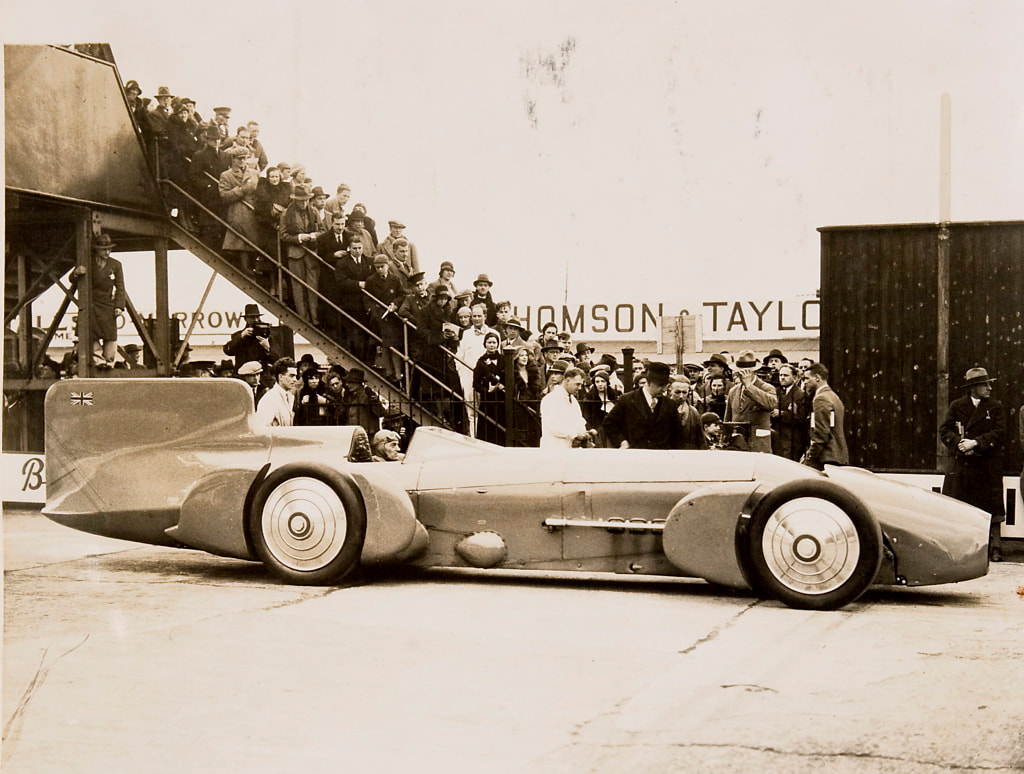

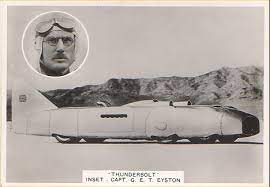

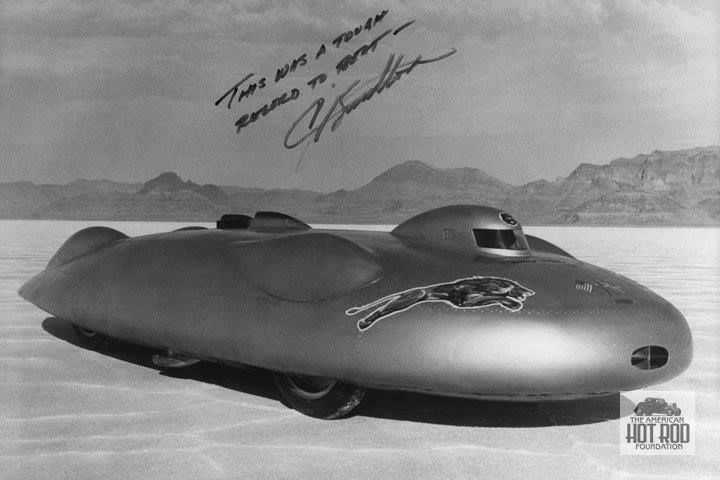

As a race, the first 199 laps of the 2001 Daytona 500 were spectacular, a race everyone had anticipated and wanted. However, lap 200 would be the one to tear NASCAR apart. The triumph of Michael Waltrip and D.E.I would be made futile as one of motorsports legends passed on in the most unexpected of ways. We watch motorsport because of its unpredictability, for its ‘lightning in a bottle’ moments. Unfortunately, like life itself, with spectacular lightning comes the darkness of clouds, thunder, and cold rain. However, the sky always clears. We just need to remember to look up. Speed. We have obsessed over it since the dawn of time. The cavemen and our early ancestors would rely on running quickly to escape predators and hunt down prey. The average human can run approximately at a speed of 13km/hr. The earliest signs of humans going faster is 5,500 years ago, when we began to ride horses, oxen, and camels. The horse would be a preferred mode of transport for centuries, and could reach speeds of 48km/hr, whilst stronger horses like Thoroughbreds and the Quarter Horse can gallop their way to 70km/hr. Humankind had domesticated a beast that would assist us for centuries in travelling, exploring, trading and warfare, and are still used today. Even through the industrial revolution, and with the invention of steam trains, motorbikes and bicycles, the horse would still be the fastest way we could travel. That changed however during the years of 1897 and 1903. The Royal Prussian Military Railway began doing high speed tests with electric trains. These experimental trains would reach 160km/hr, leaving the horse in its dust. The Gobron Brillié Gordon Bennett race car would become the fastest land vehicle as it reached 166km/hr just a year later. Our obsession for speed and the automobile would explode in the coming decades. I’m not going to go through each record breaker, as there have been quite a lot in our pursuit for pure speed, but I’ll cover the major records. In addition, here is a video showing the machines that would take us to new velocities. The next milestone would be Fred Marchriott in the Stanley Steamer, that would reach 195.65km/hr in 1906. Two wheels would have its moment in the sun almost exactly a year later, pushing the bar to 219.31km/hr with Glenn Curtis on his Curtiss V8 motorcycle. By the 1920s and 1930s, people had begun to realise that the car was here to stay, and the land speed record would rise and rise. The next record to be officially recognised would be Rene Thomas in 1924, reaching 230.64km/hr in the Delage La Torpille (above). Only two years later, J.G. Perry Thomas would pass the 250km/hr mark in the Highman-Thomas Special Babs, with a top speed 272.45km/hr. The 300km/hr mark would be surpassed only 11 months later when Henry Seagrave reached 327.97km/hr in the Sunbeam ‘Slug’. Malcolm Campbell would be the man to beat in the coming years, claiming the speed record multiple times. In 1935 at Bonneville, he would reach 484.20km/hr in his Campbell Rolls Royce Railton Blue Bird. George E.T. Eyston would carry the torch, being the first to break the 500 and 550km/hr marks in ‘Thunderbolt’. The last internal combustion powered car to hold the land speed record would be the Railton ‘Mobil’ Special (above), driven by Joe Cobbs to 634.39km/hr. From then on, jet power would be the name of the game. The Railton ‘Mobil’ Special would officially hold the record from 1947 to 1964, when during the month of October at the Bonneville Salt Flats, land speed would reach new heights thanks to jet propulsion. Art Arfons in ‘The Green Monster’ would reach an unthinkable 875.6km/hr. A year later, on the infamous salt, Craig Breedlove would return and officially break the record by almost 100km/hr. Strapped into the Sonic 1 – Spirit of America, he would be sent to 966.96km/hr. 5 years later in 1970, Gary Gabelich in Blue Flame would break into the 4 digits, with a speed of 1014.52km/hr. The record would be pipped in 1983 in the Black Rock Desert, as Richard Noble and his British based team would reach 1019.47 with the infamous Thrust2. The Thrust2 would be the framework for Noble’s next record breaker, the Thrust SSC, driven by Andy Green. On October 15 in 1997, the Thrust SSC team would make two runs at the Black Rock Desert in Nevada. Green would begin slowly to avoid sucking the earth into the turbofans. At 80mph (128km/hr) Green would put his foot down. As he ripped through the desert and as his speed ascended, the car would begin to fishtail, and Green would gently counter steer to keep it straight. After two runs to make it official, the Thrust SSC would reach 1227.99km/hr, breaking the sound barrier in the process. Today, Richard Noble and Andy Green lead a new project, the Bloodhound SSC/LSR, and they’re aiming to reach 1000mph (1609km/hr) to leave the current land speed record far in the dust. Unfortunately, Covid-19 and financial issues have burdened the project, but so far they have reached a top speed of 628mph (1010.67km/hr). I very much hope they can break the 1600km/hr mark. To be able to witness that in my lifetime would be extremely special, and a perfect example of what we love to see. Humans doing the unthinkable, the extraordinary and pushing the boundaries of physics.

I don’t like thinking about ‘what ifs’ in motorsport. There are so many variables and little things that affect race results, and the performance of teams and drivers. For instance, what if Mark Webber didn’t crash at Korea in 2010, would he have won the championship? However, there is one ‘what if’ that I often think about, not because I wish it didn’t happen, but because I think it is one of the most influential events to shape motorsport. Let me explain: This is Roger Penske. He was a racing driver in the 1960’s, first doing hill climbs and then began racing Porsches. He competed in two Formula One grand prix and won a NASCAR Late Model race, becoming a well-known racing driver. In 1965, he got offered a rookie test for that year's Indianapolis 500. However, he instead turned it down and retired as a racing driver, turning to business with Chevrolet at a dealership in Philadelphia. This change in venture would help Mr Penske start his own race team, entering the Indianapolis 500 for the first time in 1969. By 1971, Penske were working with McLaren on the M16, a next generation car. By 1972, Team Penske won their first of many Indy 500’s with the dominant McLaren. Team Penske would soon start building their own cars and would win their first IndyCar championships in 1977-78 with Tom Sneva and 1979 with Rick Mears. Mears would also claim his first of four Indy 500 victories in 1979. Penske would continue to be the team to beat into the 1980’s, winning the championship with Rick Mears (1981, 1982), Al Unser (1983, 1985) and Danny Sullivan (1988). They also would win an extra 5 Indy 500’s during this time. After two more wins in the 500 in 1991 and 1993, Penske would build the PC23, one of the most dominant open wheel race cars in history. Not only that, but they had a top-secret ace card up their sleeve for that year’s Indy 500. With the leadership of Roger Penske, a loophole was found for the PC23 to run the powerful Mercedes 500I engine for that race only. And it again dominated. Team Penske have continued to be the most successful team in American Open Wheel Racing, winning 16 championships and 18 Indianapolis 500’s. But IndyCar wasn’t Rogers only foray. Debuting his NASCAR team in 1972, it would only take a year for them to get their first win with Mark Donohue. Team Penske would win the Cup Series Championship for the first time in 2012, and again in 2018 whilst they would claim the Xfinity Championship (the second tier series) in 2010 and 2020. Since Roger Penske started his team in 1965, he has also delved extensively into sports car racing. Throughout the team’s history they would compete in Trans-Am, the United States Road Racing Championship (where they would claim the championship in 1967 and 1968), and Can-Am, winning the championship in 1972 and 1973. They would also try their hand at Endurance Racing, competing at the 24 Hours of Le Mans and surprisingly winning the 24 Hours of Daytona in 1969. With Porsche, Penske would claim the American Le Mans Championship from 2006 to 2008. More recently, they have competed in the IMSA championship with Acura and the World Endurance Championship. Roger Penske would also lead a team into the world of Formula between 1974 and 1976, scoring one victory. Recently in 2015, Penske would team up with Dick Johnson Racing in the V8 Supercars championship. They would dominate, winning three straight championships in from 2018 to 2020 with Scott McLaughlin, and would claim the 2019 Bathurst 1000 crown. Now, Roger Penske is the owner of Indianapolis Motor Speedway and the IndyCar Series, and I couldn’t imagine a better person for the job. His legacy and influence in motor racing is of mammoth unmeasurable proportions, and has built one of, if not the most successful team across all motorsports. All this because he turned down the rookie test in 1965 to focus on business with Chevrolet. Imagine if he hadn’t. But that is only half of the ‘what if’. Because guess who replaced Roger Penske at that Indy 500 rookie test in 1965. Mario Andretti. You could know absolutely nothing about racing, and you still would have heard the name… Mario Andretti. The Italian-born American is one of the most versatile and successful drivers in motorsport. His career spans half a century. He was awarded U.S Driver of the Year in three different decades, was the first driver to win IndyCar races in four decades and the first to win in any motorsport category in 5 consecutive decades. Mario and his twin brother Aldo began their American racing careers on the dirt tracks of Pennsylvania. Across 1960 and 1961, Mario Andretti would grab 21 wins across 46 in modified stock cars. From 1961 to 1963, he raced in midgets and would make his IndyCar debut in 1964 whilst also racing in sprint cars at the same time. His long IndyCar campaign would truly begin when the aforementioned Roger Penske would turn down the rookie test for the 1965 Indy 500, allowing Andretti to take part instead. He would finish third in that year’s race, earning him rookie of the year honours. He would also claim the IndyCar Championship in 1965 and 1966. In a year-old car, Andretti would claim his only Indianapolis 500 crown (1969) and that year’s championship. During this time, Andretti would compete in 14 NASCAR races, and would win the 1967 Daytona 500. Beginning in 1968, Andretti would drive part time in F1, as well as the Can-am series for three years. He would also have a go at American endurance racing, winning the Sebring 12 Hour three times and the Daytona 24 Hours once in 1972. 1975 would be the first year competing full-time in F1. With help from Colin Chapman and ground effects, Andretti would dominate the 1978 Formula One World Championship. He would return to IndyCar in 1982 and would win the championship again in 1984. Mario Andretti had multiple attempts at the 24 Hours of Le Mans, with his best finish being second overall in 1995, although it is important to note Andretti and his teammates finished first in their class. However, his legacy is more than just his wide foray of wins and the many categories of motorsport he has competed in. The Andretti legacy continues in the form of sons Michael and Jeff, grandson Marco and nephew John. As drivers, they had varying degrees of success. Son Michael would be very successful in IndyCar, winning the championship in 1991. Michael Andretti’s team would begin as Andretti Green Racing in 2003. They are one of the top teams in IndyCar and have won the championship four times and the Indianapolis 500 five times. At the end of 2009, a restructure led to the team being renamed Andretti Autosport.

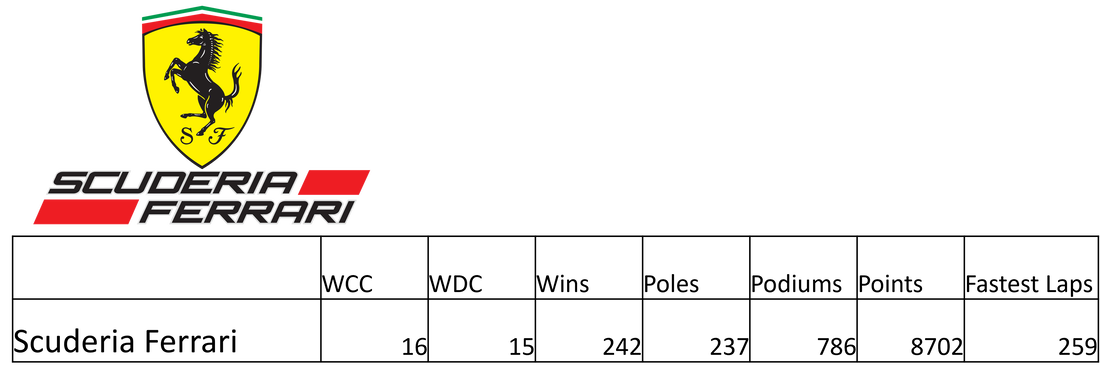

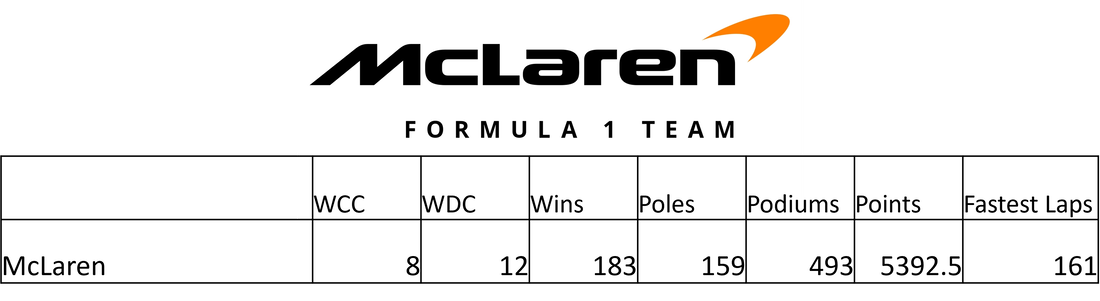

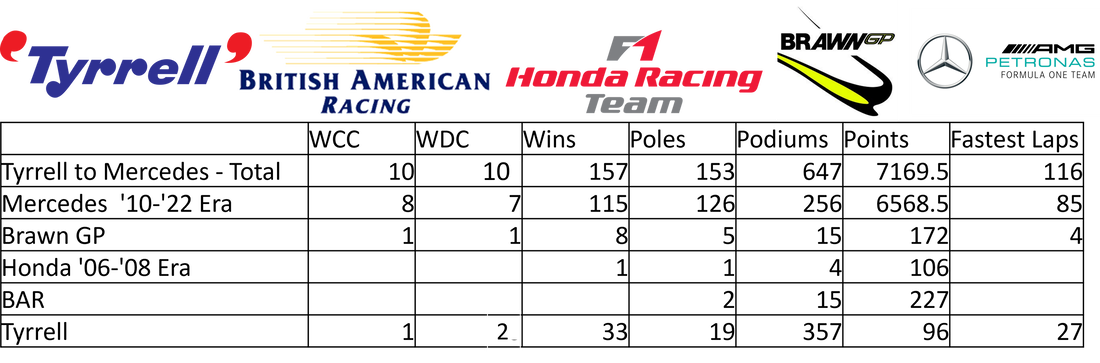

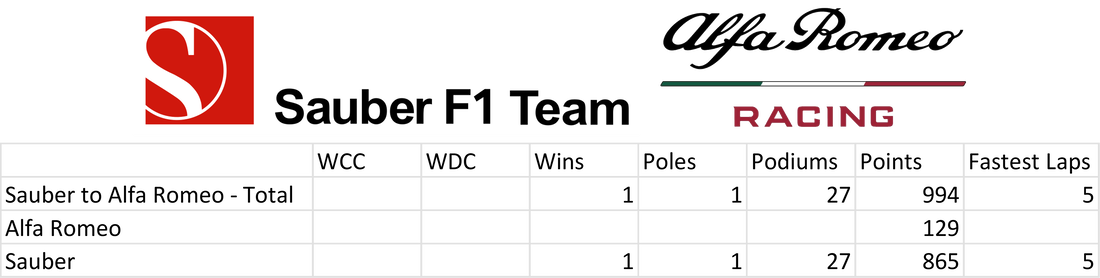

The team expanded to the American Le Mans Series for 2007 and 2008 with Acura. Andretti Autosport would also compete extensively in junior categories on the ladder to IndyCar. They have now expanded to V8 Supercars with Walkinshaw, Formula E and various Rallycross championships. Andretti are also interested in setting up a Formula One team by 2026. So, you see, Mario Andretti’s legacy is more than just his versatility behind the wheel of a race car, it has spawned a family of racing drivers and an internationally successful team. I wonder what would have happened if Roger Penske took the rookie test and entered the 1965 Indy 500? How much different both Andretti and Penske’s careers would be. One thing I’ve learned after watching so much motorsport, is that one small decision or occurrence can have a massive impact. In this case, I don’t think Team Penske would exist or have been successful if Roger Penske had continued to race. The same goes for Mario Andretti. Would he have been able to have such a long and successful racing career that would eventually lead to another widely participant race team? I doubt it. But, because Roger Penske retired from racing and changed to business, giving Mario Andretti his big chance, the rest became history, and we are only left to wonder, 'what if?' I have attended at least one day at the Australian GP ever since 2007. One highlight early, although not so much now was getting and reading the Race Program. Now, they lack information and colourful infographics with teams history and a full detailed entrant list. As a young F1 fan, something I never understood was that when a team changed names, their statistics would be put back to 0. Also, history would barely mention previous teams names from the same factory, but would mention Renault being around in the 80’s, whilst having no mention of Benetton or Toleman, even though they were teams from the same base. Another example is the team from Faenza Italy. The outfit originally called Minardi has two home gp wins, yet neither under Minardi statistics. One under Toro Rosso and the with Alpha Tauri. I have found some websites that will combine the two teams’ stats, but it’s not always the case. Also, when Hamilton left for Mercedes for the start of 2013, no one thought he would ever win, even though they had dominated the championship in 2009 with barely any resources. Yet, it was a different team name, so everyone had seemed to have forgotten about Brawn GP. And don’t get me started on the Force India and Racing Point fiasco either! So, to get it off my chest, I decided to compile all the stats from each team on the grid, including all their name changes. For simplicity, we’ll start off with the four teams who have never had a name change. Please note these statistics are as of the 2022 French GP First up, we have Ferrari and McLaren, the two most successful teams in F1 History and long-lasting teams in the sport. Ferrari have won 16 Team championships, the last time being in 2008, and 15 driver's titles, the last being in 2007 with Kimi Raikkonen. They have competed in over 1000 races, and has been one of the most dominant teams in parts of history, including six straight team championships in-between 1999 and 2004. Ferrari is more than a team, it expands into the spiritual significance of Formula1. I don't think anyone can imagine F1 without the Scuderia. McLaren was began by the New Zealand driver Bruce McLaren, who early in his F1 career drove for Cooper. He would compete under his own team from 1966, and the team has been around the paddock ever since. Another mammoth team is Williams. After two unsuccessful attempts at starting a team, Frank Williams moved to Didcot and was joined by Patrick Head to create Williams Grand Prix Engineering in 1977. Although they were the butt of the joke in the paddock, that all changed when they won the championship in 1980. Williams would have plenty more success in the 1990's, being at the front of car design for a large portion of the decade. However, since then, they have become a midfield back marker team, scrapping for points. Their last win was the 2012 Spanish Grand Prix, which came as such a surprise, that the Williams garage caught fire afterwards. Haas is the newest team to join the F1 grid (and has no relation to Haas-Lola of the mid-eighties). Started by NASCAR team owner Gene Haas, and led by Guenther Steiner, the team has had a tumultuous history in F1 so far. Straight out of the gate however, they had quite a quick midfield car. However would be marred by inconsistency and bad luck over time, seeing them become a backpacker team. What certainly didn't help was when Rich Energy pulled their sponsorship, a sponsor that was and still is littered with red flags. In 2021, Haas was struggling very much financially, and had the slowest car on the grid by some margin. At the start of 2022, Haas terminated its sponsorship from Russian company Uralkali and dropped Russian driver Nikita Mazepin due to the war in Ukraine. This year, Haas have returned to the points on multiple occasions. Nothing can seem to stop this team. Mercedes have been the most dominant team in recent history, scoring 8 team championships and 7 drivers titles in a row. However, they began as Tyrrell in 1970. Jackie Stewart would win two of his championship in 1971 and 1973. Eventually, the team was bought and renamed British American Racing for the 1999 season. A lot of money was thrown around and a lot of hype was created by the team. They even predicted to win from pole on the first race of the season. However, they had a woeful first season, with a terribly unreliable car. In coming years, the team would get better, eventually scoring 15 podiums. In 2006, Honda took over, and despite getting one win, by 2008 unreliability and inconsistency had struck the team again, and Honda pulled out. Ross Brawn bought the team, worked his magic with the new technical regulations of 2009, stuck a Mercedes engine in the back and ended up winning both championships in strong fashion. Mercedes took over the team in 2010, and the rest is history. In 1997, Jackie and Paul Stewart entered Stewart Grand Prix onto the Formula 1 grid. Although their first two years they struggled with reliability, it would be in 1999 where they would grab multiple podiums and even a win at the European GP. For the 2000 season, Ford bought the company and renamed it Jaguar. Throughout 2000-2004, they only scored two podiums, then was bought by energy drinks giant Red Bull. Overtime, Red Bull slowly improved until 2009 when they had their breakout season thanks to Adrian Newey's brilliant car designs. They would finish second in the teams championship, then would have a run of 4 straight team and driver championships with Sebastian Vettel. From then on, they would be known as one of the big three teams, and last year won their fifth drivers championship with Max Verstappen, and are looking to repeat their success again this year. The team we now know as Aston Martin love a name change. The team began as Jordan in 1991, and would score a handful of points in their first season. Despite a few seasons of reliability woes, they would score their first podium in 1994. Jordan's best season came in 1999, scoring multiple wins and finishing third in the teams championship. Despite a few more podiums in the coming years, by 2006 the team would be bought by Midland. And they scored... nothing. For 2007, the team was ran by Spyker, and despite having an awesome livery, they only scored a single point. The following year the team would change hands and names again, this time to Force India. Giancarlo Fiscichella would score their first pole at the 2009 Belgian Grand Prix, and the team would slowly rise from back marker to a strong midfield team. In 2018, the team was in serious debt. Lawrence Stroll came to the rescue and bought the team, however because he wanted a name change, the team was stripped of all its points it had scored so far that year. Bizarre right? In 2019, the team would fully change to Racing Point, and would score their first win in 2020. In 2021, the team's name changed to Aston Martin. They have scored one podium so far, but have mainly struggled with recent car design changes. Toleman began in 1981, and despite struggling to qualify for races and having reliability issues, Ayrton Senna would score all three podiums for the team. The team would be taken over by Benetton and would have much more success. Michael Schumacher would win two driver's championships in 1994 and 1995, whilst the team won the constructor's championship in 1995. When the team changed to Renault in 2002, they would have more success, winning both teams and drivers championship in 2005 and 2006 with Fernando Alonso. In 2011, the team would change to Lotus. They would score quite a few podiums but only two wins. The team would change back to Renault in 2016, and would be a decent midfield team. The most recent name change was to Alpine, so Renault could promote its sports cars and other motorsport endeavors. They have so far scored two podiums and an impressive win at last years Hungarian Grand Prix. Ah yes, the passionate team from Faenza, Italy. Everyone's favourite back marker underdog. First competed in 1985, the teams history is littered with reliability trouble and zero points finishes. In the 20 years under the Minardi name, they only scored 38 points, most famously on Mark Webber's debut at the 2002 Australian GP. For 2006, Red Bull bought the team, renaming it Toro Rosso and would be used for juniour development drivers. The sister team would famously win before the main Red Bull team, on a wet weekend at its home race. They would score a few more podiums in the coming years. In 2020, the team changed its name to Alpha Tauri to promote Red Bull's fashion brand. They would win again at the Italian GP that year. Finally, we have Sauber, a team that has only had one name change (thank goodness!) Conceived in 1993, Sauber has always be a low scoring points team, however would score 10 podiums until BMW joined in 2007. During 2007, they would score more podiums and in 2008 would grab their only win to date. Robert Kubica would also lead the championship for a time. Unfortunately, they haven't had much success since that year, and Alfa Romeo would fully partner up the team, changing the name in 2019.

Short Update: Due to being unable to photograph motorsport for a few months, I decided to write and publish weekly editorials. The first one came out on the 30th of July, and not one since. The reason? Having to wait only one day for the doctors to find a suitable heart donor, which left me in a sedated state for more than a week and a half. Now, the weekly editorials will now continue as planned until I'm completely on the mend. Remember to subscribe to the newsletter too so you don't miss out. Whether you really enjoy music, movies, sports or cars, there will always be classic songs or automobiles that will define your taste. Of course, being a motorsport fanatic, the same goes for bonkers racing moments that I am sure will never be forgotten by me. Here is a list of ten: Click on the titles to watch them on Youtube "They're all in the fence!"“He’s hit the fence!” “They’re both in the fence!” “They’re all in the fence!” Some moments in motorsport are such classics that all you need to do is quote the commentary, and fans will know exactly what you’re talking about. Mark Skaife’s and Matt White’s words as the three championship protagonists came through Turn 5 in the second last race of the season, held at Sydney Olympic Park is exactly that. Rain became a threat late in the race, however to only parts of the circuit, meaning the drivers would risk driving on the slick tyre for as long as possible. After a safety car due to Russell Ingall getting stuck in the tyre barrier, the field would be bunched up. As they headed to Turn 1, Jamie Whincup, Mark Winterbottom and James Courtney, the three drivers fighting for the championship would lead the field. The lack of grip became apparent at Turn 5, where the race exploded into chaos. The top teams rushed to fix the broken cars and score any points they could. Through all of this, Jonathon Webb, in his first full time season in V8 Supercars would survive and score his first victory. The championship fight would head into the final race on Sunday, but very few remember that race. The Greatest SpectacleIn 2011, my Dad and I travelled to Indianapolis for the 100th Anniversary of the Indianapolis 500. As a tiny 9-year-old, the sheer size of the Speedway was what impressed me the most. From Turn 1, all you could see were packed grandstands from one end to the other. The atmosphere of the days before the race, right until the final celebrations had ended was like nothing else. This was more than just a race, this was a month of celebrations and anticipation for what they called ‘The Greatest Spectacle In Racing’. On Lap 157, Ryan Briscoe and Townsend Bell would tangle into Turn 1, bringing out the caution. A handful of drivers would pit, hoping to make it to the end, including JR Hildebrand and Dario Franchitti. Franchitti would be hoping for another caution to be able to go to the end without having to pit for more fuel, whilst Hildebrand would save fuel early in the stint in an attempt to go all the way, even if there was another caution. Many others however would pit with 21 laps to go but would have to push all the way to get to the front. It would be 20 laps of tension. Nobody could predict who would win or who would run out of fuel. If you don’t know the result of this infamous race, I suggest you watch the final 20 laps if you have time, just for a larger context. But above is just the final 5 laps. Either way, you won’t forget how it ends in a hurry. Barbagello's Ball of FireAs the cars drove around for the formation lap, there were plenty of questions being thrown around for Race 8 of the 2011 V8 Supercars championship. Could anyone beat Whincup? What could Bright do from the front row? How would teams and drivers manage the softer compound of tyre? And what action would we see at the busy turn 1? As the red light went out, Whincup and Bright got an even start. Behind, Alex Davidson rocketed off the line from fourth, diving to the inside to make a move at Turn 1. But the question of what would happen at Turn 1 was forgotten. All eyes became fixated on the seventh row of the grid. What would be a shock to everyone, the rear of Karl Reindler’s car lifted off the ground and exploded in a fireball. He had stalled on the grid, and Steve Owen had arrived on the scene with nowhere to go. This would mark many changes in the regulations, particularly with fuel cells being moved forward and made safer. And no one who was watching that day will ever forget it. The First NASCAR Race I RememberMy first memory of NASCAR was the final laps of the 2009 Coke Zero400 at Daytona. I didn’t know any of the drivers and teams, and at the time had no real basic knowledge of NASCAR. However, the final lap crash would always be in my mind, a motorsport moment I would never forget. Luckily, I recently found the actual race details on Instagram, which means I can share it with you. It introduced me to the polarising way of racing in NASCAR. Rubbing is racing, and drivers will literally take out or be taken out by rivals in order to win the race. Contact is not only tolerated but, in some cases, encouraged, so that fact left quite an impression on me, and this race was the first example I witnessed. The Greatest Great RaceNot only was this a crazy race from start to finish, with plenty of drama, but it had one of the greatest closures to a race ever. Scott McLaughlin and Shane van Gisbergen, the two front runners of the day were both taken out of the race late as they both became victims of the endurance. On the other end of the spectrum, Jamie Whincup and Paul Dumbrell would start from 23rd and charge through the field, recover from a spin and charge to the front again. Chaz Mostert and Paul Morris would start dead last, would stick it into the Turn 2 tyre barriers, but would be there in the end to do battle. After one last safety car, the two other contenders Lowndes and Winterbottom tangled at Turn 1, leaving it to Whincup and Mostert to battle it out. Mostert had enough fuel to go to the end, whilst Whincup was being told to save, although it seemed futile. What eventuates is a heart-in-mouth final set of laps. The commentary has already become a classic, yet it was also informative, stirring in the heat of battle and definitive. The battle for Australia’s greatest motor race would come down to the wire. Kristaps Blušs First FD WinAfter reading and being introduced to the sport of drifting via Speedhunters.com, I began to vaguely follow the Formula Drift series in the US. One event I remember watching attentively was Round 3 of the championship at Road Atlanta. Seeing many of close battles and insane driving and smoke shows, and an eventual first-time winner, it certainly influenced me to go try and photograph drifting the next year. The video above is a medley of all Kristaps Blušs' winning runs, defeating the heavyweights of James Deane, Piotr Więcek and eventually Fredric Aasbø. As he was declared the winner, he climbed atop his mental carbon fibre BMW M3 E92, punching the air in relief. After climbing down from the top of his car, he relaxes yet heaves a cry. ‘F***ing finally!”. Yep, that sums it up perfectly! Right Down to The Wire at Watkins GlenThis wasn’t a race I watched live, but one that my Dad showed me later. Being an Aussie, I’ve always supported the Australian in a particular series and in NASCAR, Marcos Ambrose was that Australian. Not only did he win this race, but in spectacular fashion against the likes of Brad Keselowski and Kyle Busch. It would be a battle until the final corner, with some of the most ragged-edge driving I’ve ever seen. Ambrose and Keselowski ran on the fine tightrope of grip, making for one of the greatest finishes in NASCAR’s recent history. VicDrift RD 1 2019The first round of the 2019 VicDrift Championship would be not only my first introduction to grassroots drifting, but also my first event holding media credentials. With a lineup of 61 cars attempting to make the Top 32, plenty of awesome cars and brilliant drivers, it was impossible for me not to get hooked. The battles at night were down to the wire with drama and dust and smoke being thrown in all directions. Above is a video by Racing Line Australia, documenting Dale Campaign’s victory that night. If you look closely, you can see a dorky me, camera in hand, wearing a hoodie with backpack constantly strapped to my back. Heartbreak for McLaughlinA season long battle between Jamie Whincup and Scott McLaughlin would be decided in Newcastle, with two races to go. McLaughlin would win from pole in the Saturday race, meaning if Whincup won the race on Sunday, McLaughlin would only have to finish 11th to secure the title. Grabbing pole for the final race meant it was McLaughlin’s championship to lose. He already had one hand on the trophy. However, in the race, McLaughlin would get a drive-through penalty for speeding in the pits and whilst coming back through the field, contact with Simona De Silvestro would give him another. At the restart, he was sandwiched and would end up being rear-ended. With the damage slowing down his car, he'd end up fighting for exactly 11th with a few laps to go. Triple 8 Racing however would have an ace up their sleeve. By pitting Lowndes late, he would charge through the field. If McLaughlin was overtaken by Lowndes, it would all be over. What eventuates cannot be scripted. Ricciardo's Chinese MasterclassWatching your favourite driver literally destroy the competition is always awesome, but particularly when it comes out of nowhere. Ricciardo would be P6 for the majority of the race, however he wouldn’t finish there. After the two Toro Rossos collided at the hairpin, the safety car was deployed so marshals could clean up the debris. Bull would bring both their drivers in immediately, putting them on softer, grippier rubber for the final stint. As Ricciardo would finesse his way up the field, each overtake being better than the previous, Verstappen would show impatience and would eventually bulldoze Vettel at the hairpin. With a ten second penalty, he was out of contention for the race win despite having fast, fresh tyres. Lap after lap Ricciardo would bring himself closer to the front, and with a ballsy late lunge on Valterri Bottas, he would take the lead, demonstrating an overtaking masterclass.

|